The last of the Teenage Scribblers - Our quick reaction to the UK Budget

Views From the Marsh - David Owen

It was Nigel Lawson, the then Chancellor, who coined the term teenage scribblers to describe the work of city economists in the 1980s; especially when they disagreed with his much more upbeat view of the outlook.

Back then the Budget Red Book was much smaller, in some ways making it much easier to zero in to pen something hopefully of interest, that would be hand delivered by waiting motorbike messengers to clients in London (including Downing street) and faxed to clients, internationally.

Now we have the detailed independent analysis of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). But that does not mean that we will necessarily agree with all the big judgement calls they make (as ever, economics is far from an exact science).

What then should we make of Rachel Reeves’ first Budget?

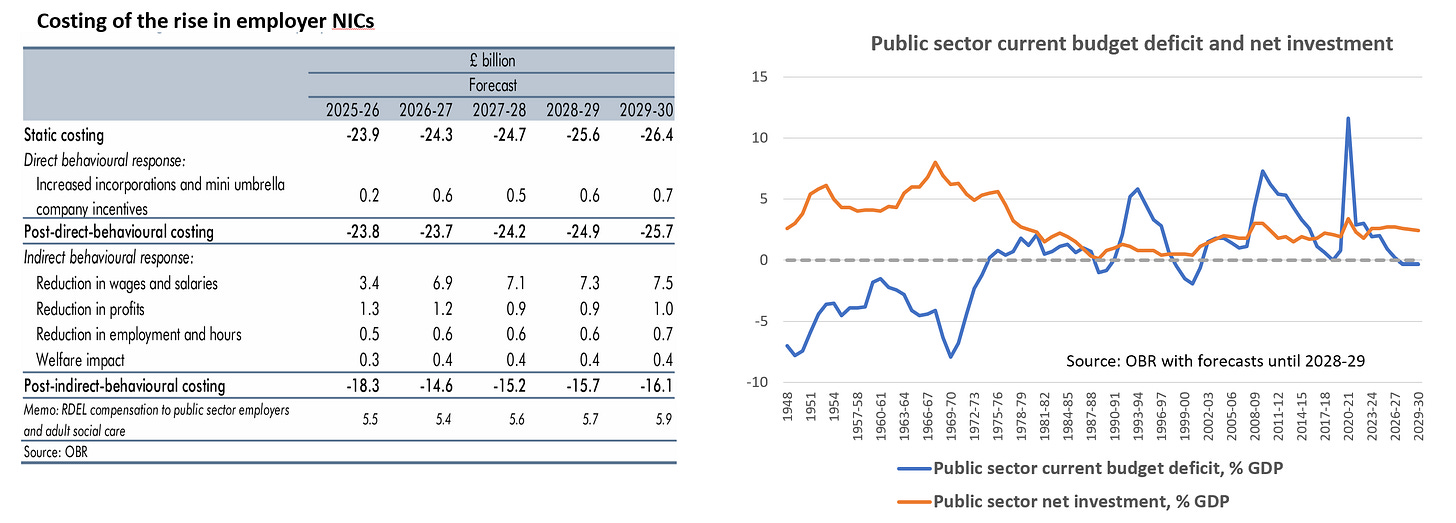

The first point to emphasize are the headline grabbing rises in public spending (£69.5bn a year over the next 5 years, with £45.6bn going on current spending and £23.8bn on capital expenditure), rises in taxes (£36.2bn, in large part due to an increase in taxation on many companies employing labour - the increase in employers’ NICS rate and reduction in its threshold, raising almost £26bn), and increases in public sector borrowing (£32.3bn on average over the next five years).

This comes on top of a further significant rise in the National Living Wage (NLW, 6.7% from next April to ensure its level remains at two-thirds, or more, of median earnings, and a 16.3% increase for 18-20 year olds), that was also announced this week - but, not being a Budget measure was not included in the OBR’s analysis, even though in combination with employers’ NICs it could clearly have a significant impact on certain sectors of the economy.

The first judgement call by the OBR was that UK companies react to the significant increase in employers’ NICs by resisting pay demands (to keep their overall labour costs down), so squeezing real wages.

This can be seen in the table below. This is a key reason why the OBR is looking for wage inflation to moderate to only 2.1% in 2026; a very similar forecast for wage inflation as the BoE (arguably, in part to be consistent with their CPI inflation target).

However, in combination with a significant rise in the NLW, we expect the second-round impact in employers’ NIC to be more equally shared between profit margins, prices, employment and hours worked, as well as wages, than suggested by the OBR.

It should not be forgotten that the UK labour market, in a historical context, remains relatively tight, with significant labour market mismatch.

True, many of the companies likely to be most impacted by the changes may already be operating on very thin margins and perhaps running at an operating loss.

But, other companies, in contrast, may be operating in a very different space and could push through the increased costs, in the form of higher prices. Many companies may not be directly impacted by the rise in NLW at all.

Moreover, the rises in employers’ NICs and the NLW should be taken in the round, against the backdrop of a significant increase in public sector investment, forecast to rise by almost the same amount as NICs raise in additional tax revenues.

Contrary to some headlines, as a central case the OBR is assuming that this directly crowds in some private sector investment (pages 81 to 84, of their Economic and Fiscal Outlook). Overall business investment only ends up lower on their forecast, because interest rates are higher than would otherwise be the case, and profits come under pressure.

However, in reaction to everything that is going on we expect many companies to substitute capital for labour. This may not be possible in sectors like hospitality, but (along with the full expensing of qualifying expenditure and R&D tax credits) overall investment (and to a lesser extent, real household disposable incomes) could end up higher than the OBR is forecasting.

Ultimately, we may quickly see increased company failures in some sectors, but over time increased company formation in other areas. (Remember there is also relatively a lot of cash sitting on the sidelines.)

We have seen comments to the effect that a balanced current government balance is not consistent with increased public sector net investment, the government needs to run a very large surplus.

However, as the chart below shows this is not the case. Public sector net investment is not forecast to return to levels last seen in the 1950s and 1960s.

Please consider becoming a paying subscriber to continue reading on, where we discuss the implications for interest rates, in particular - remember that there is a key MPC meeting, including publication of the BoE’s Monetary Policy Report, revised forecasts, and perhaps more scenario based analysis, next week.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Saltmarsh Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.