Less than five weeks ago, on 12 September, the ECB made a minor change to its quarterly growth and inflation forecasts, and cut interest rates for the second time in this cycle, to 3.50%. At the accompanying press conference Lagarde saw no reason to pre-commit to a specific timeline for future action and sounded fairly relaxed about the idea of the ECB potentially waiting until December to cut rates again. Yet, only a month on, the markets are now pricing in close to 150bp of easing from the ECB over the coming year, with the Governing Council preparing to cut rates both in October and in December. What’s behind the ECB’s rethink and how is Lagarde likely to frame this week’s rate cut?

Our view is that those looking for the ECB to deliver a dovish policy pivot this week will be disappointed. Instead, as the she did in July and in September, Lagarde is likely to say that the ECB is becoming increasingly confident about the inflation outlook, which means that policy can be adjusted accordingly.

In reality, the news on inflation over the past month would not have actually moved the dial on the Governing Council too much. Yes, September saw a large drop in the headline rate due to energy prices and base effects. Also, for only the second time this year we saw a genuinely weak monthly print for core inflation. However, services inflation, something that the Governing Council focuses on as a better measure of domestic inflationary pressures, remains stuck at 4% YoY, close to where it has been over the last eleven months.

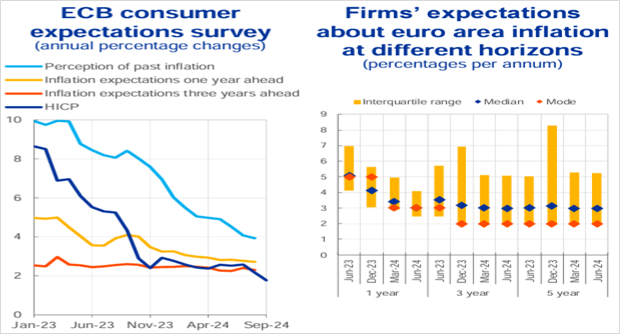

What signal is the ECB responding to? Domestically, the Governing Council would have been encouraged by the slowdown in the growth in negotiated wages for Q2 (although the ECB expects to see a bounce back in these figures in the second half of the year), as well as a decline in consumer and market inflation expectations, as recently highlighted by both Philip Lane and François Villeroy.

Consumer and business inflation expectations in the euro area

Source: ECB

However, by far and away the most important swing factor is that there is now more clarity about the outlook for the US Fed. Only a few months ago it was not certain whether the Fed would ease policy at all in 2024. Now, the markets expect 100bp of cuts this year, followed by another 100bp in 2025.

Inevitably, market rate expectations will move around. But against the backdrop of other global central banks moving in the same direction, the domestic economy forecast to see sluggish growth and the balance of risks around inflation shifting, there are fewer reasons for the ECB to keep rates in restrictive territory.

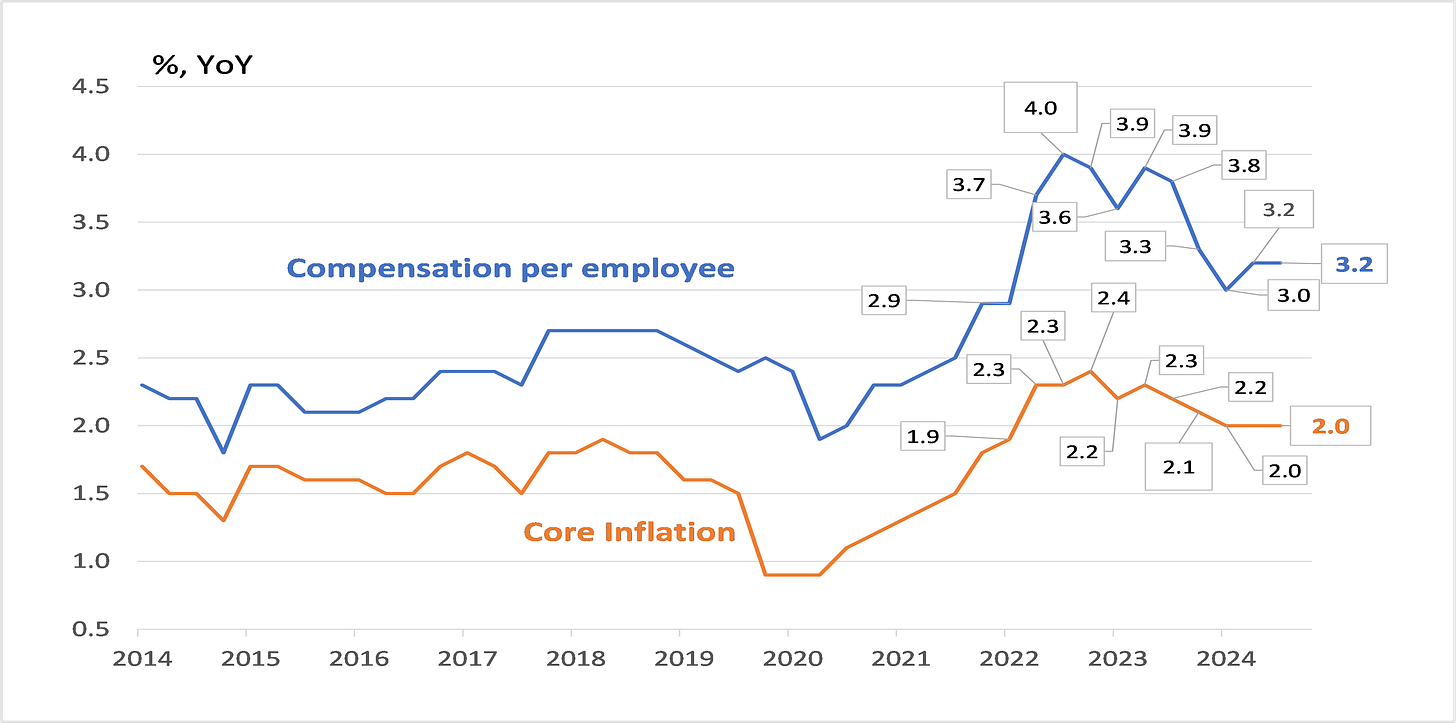

Lagarde will, of course, brush aside the point about the Fed and remind the journalists about the ECB being independent. Instead, she is likely to argue that the ECB’s September forecasts already had core inflation at 1.9% in Q4 of 2026 – a clear enough signal that further easing was in the pipeline – and the incoming data simply gave the Governing Council an opportunity to deliver a slightly earlier rate cut.

End-point of the ECB’s forecasts for wage growth and core inflation (the final data points in the chart are the ECB’s year-average forecasts for 2026, published in September)

Source: ECB and Saltmarsh Economics

Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to our work. And send us a message if you would like to receive our full research report on this topic.

© 2024 Saltmarsh Economics Limited company Number: 13681146

Registered Address: Zeeta House 200 Upper Richmond Road, Putney, London, United Kingdom, SW15 2SH

Saltmarsh Economics is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.