Could a significant shift in central bank reserve portfolios be underway?

Views From the Marsh - David Owen

We will be looking at the issue in a post later in the week, when we examine the risks surrounding private markets (that the IMF and others have been warning about for a long time), but full transparency can be a double edged sword.

In some situations full disclosure can be a very good thing; on other occasions it can cause investors to run to the hills. This became very apparent to us in the euro area crisis - but more on this later in the week.

However, a lack of transparency in periods of uncertainty can cause investors to demand a much higher risk premium for holding the assets in question. Indeed it can be another reason for going underweight an entire asset class, if one does not know exactly who may be most at risk.

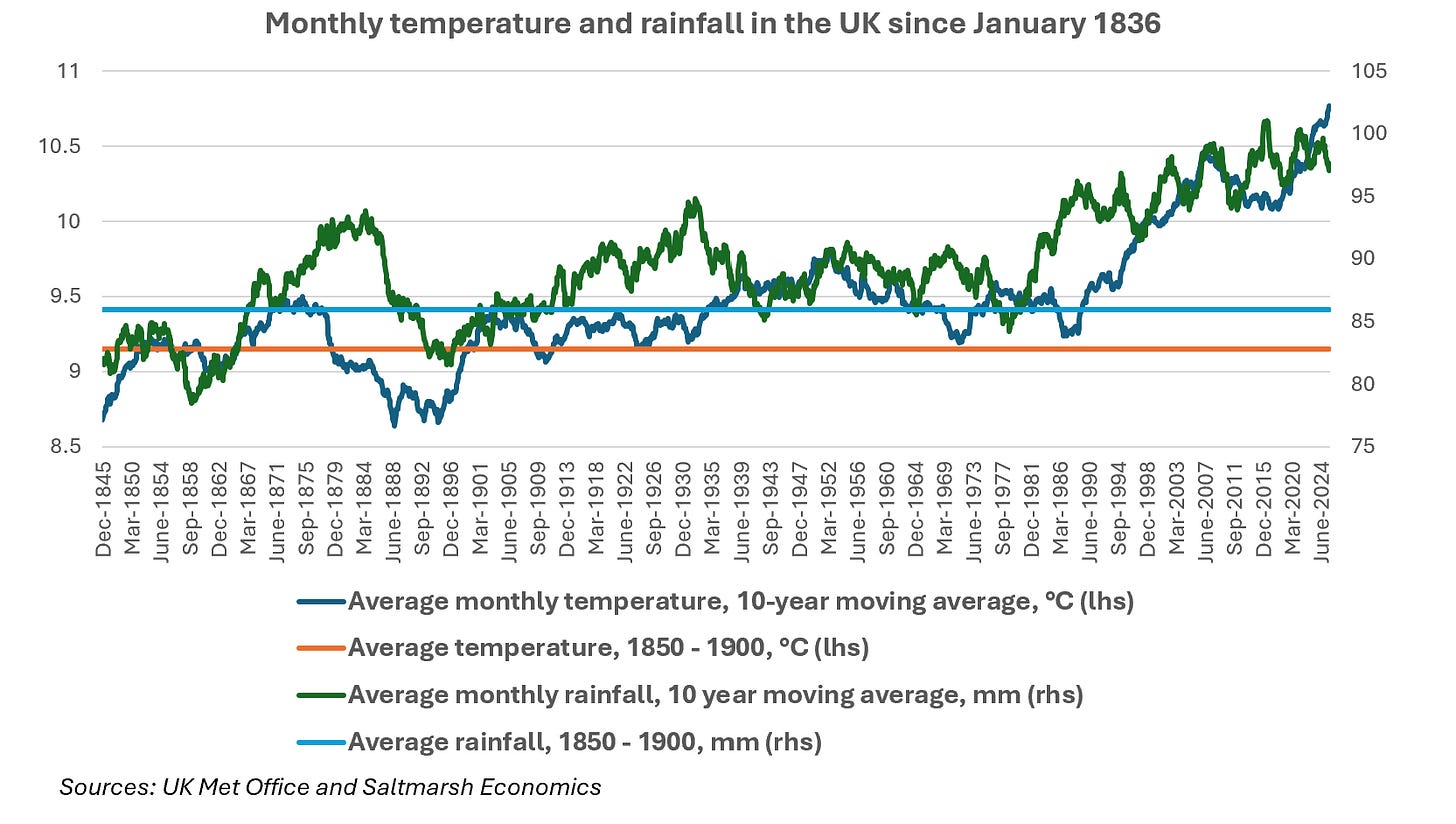

US government agencies no longer publishing detailed data on the estimated economic costs of natural disasters will not stop climate related events happening, in a warmer and wetter world (see first chart below; note the UK Met Office data on temperature goes back to 1659, that on rainfall back to 1836).

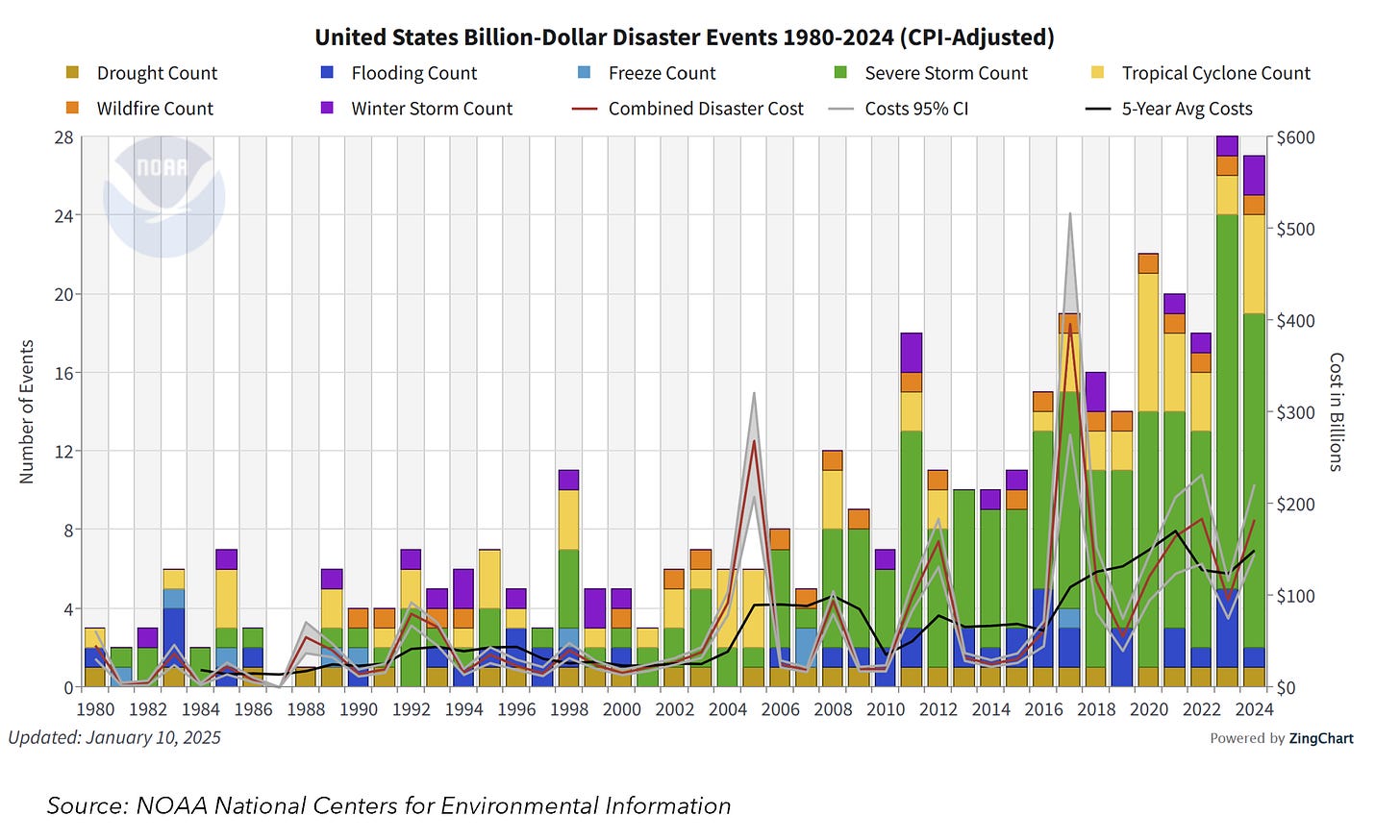

But it could be a further reason for investors attaching a higher risk premium to holding US assets, especially given what had been what had been the high granular quality of the previous official data, showing the estimated costs of natural disasters drilled down by US state, almost in real time - very useful information for anyone, for example, thinking of investing in US credit or equity, bonds issued by US state, underwriting a loan against collateral, or insuring a business or piece of commercial or residential real estate, if we are moving into a world of more frequent and extreme climate related events.

As things stand, the US scores relatively poorly on our very own Saltmarsh Economics Climate Index (SECI), which ranks sovereigns of climate grounds, in large part on the back of its emissions.

The US also scores poorly on its official estimates of reported disasters (which set the hurdle for the economic cost of any individual disaster being counted, as at least $1bn) - see chart - skewed towards a few US states.

What we do not know is the extent to which this was a reporting issue - a function of how many natural disasters are insured, with no estimates of the economic cost (as opposed to the human cost) of climate related events being recorded, in the case of some countries, at all. But, at least we were previously able to have an official estimate of reported disasters in the US, that we could have confidence in - especially important if these events are to become more frequent and costly, and potentially increasingly skewed towards a few states.

But, there is one class of investors that could play an increasingly important role in all such things - central banks.

At present there is much talk of how much certain central banks could be switching out of dollars into gold - reminiscent of the French supposedly stockpiling gold from 1965 onwards (when it was fixed at $35 an ounce), before the eventual breakup of Bretton Woods in 1971, and gold prices rising to over $850 an ounce by 1980, before falling back again.

But not exactly under the radar - because many central banks are making it very clear how they are thinking about the issue - more and more central banks are ranking sovereigns on their climate footprint.

This is true of both their QE portfolios (the paper of their own sovereign), as well as their own reserve portfolios - which in some cases will be relatively extensive, and include the paper of other countries (coming in some cases, paper with much higher carbon footprints).

Could this be another reason for central banks to hold fewer dollars?

We will be addressing the subject in a much more detailed research note, but behind the paywall give more examples of the potential direction of travel.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Saltmarsh Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.