As ever, much of our latest thinking on the BoE will be held back behind the paywall of this post.

But what we can say at this point is that, on balance, we were disappointed by the level of detail contained in their “new improved” Monetary Policy Report – little sign of a reset there, despite the recommendations of the Ben Bernanke Review. We will be writing more on the BoE, after the BoE’s Watchers’ Conference hosted by Kings College London, tomorrow.

Understandably perhaps, much of the discussion about the UK Budget to date still focuses on the sectors most likely to be impacted by the increase in employer national insurance rates, and the number of family farms likely to be caught by inheritance tax - in the case of the latter, another text book example of government ministers and officials, and their advisors, not engaging enough with the industry concerned, before announcing changes. (House building targets are another - just announcing a number doesn’t mean it can happen.)

However, the Budget should also be seen against the context of an incoming government hoping to address the UK’s low rate of productivity growth, by raising both public sector net investment and private sector investment, and doubling down on net zero (admittedly on a narrow definition of emissions - at the last count, over 50% of the UK’s carbon footprint were embedded in imports of goods and services).

But this will also require further subsidies, and further investment in the infrastructure, to further reduce targeted emissions. That much is obvious.

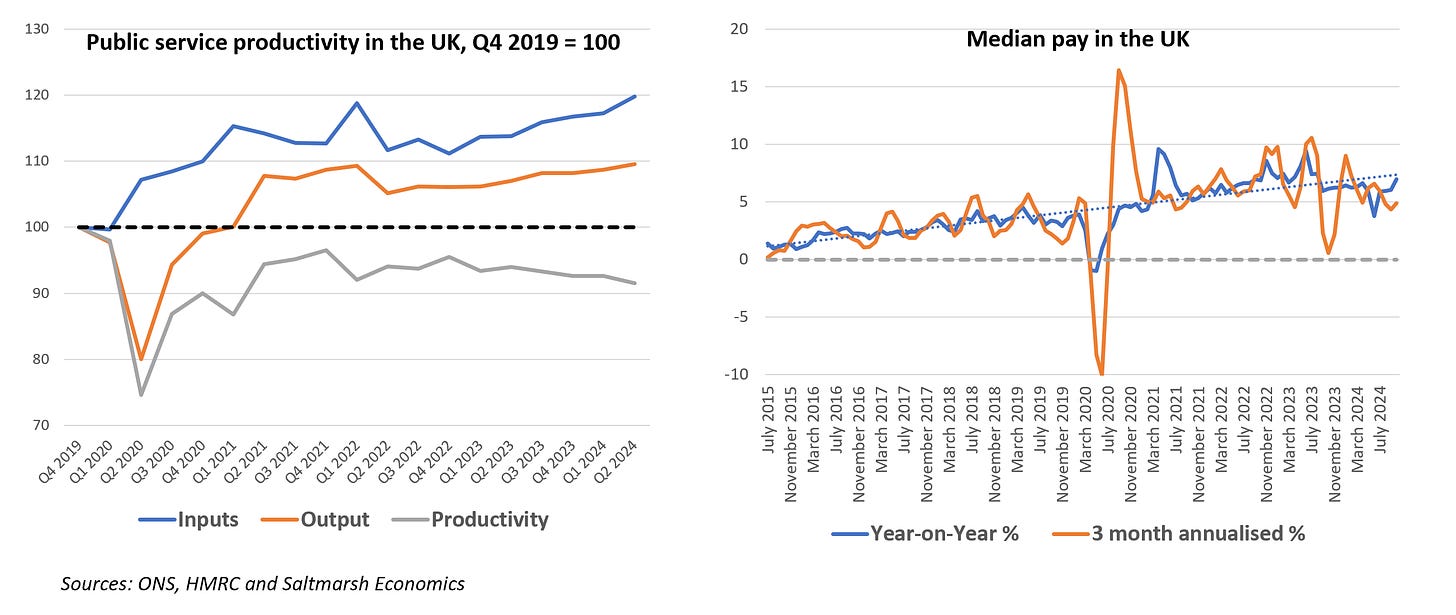

Recent data releases again highlight the UK’s comparative advantage in parts of services where the UK enjoys a large trade surplus with the US, as well as the on-going weakness of public services productivity. Taking account of inputs and outputs, this fell again in Q2, and was 8.5% lower than in Q4 2019. This is also an area that clearly needs addressing. And is another good example of targets not working, or creating perverse incentives.

A renewed focus on investment may be nothing new, but is very much consistent with what Rachel Reeves’ Chair of Council of Economic Advisers, the LSE’s John Van Reenen, has been advocating. One thing is clear. This will not be the end of the story.

In fact, in amongst a weak looking UK GDP release for Q3 (0.1% on quarter), business investment rose by 1.2%, and 4.5% on the year. Importantly, there is a relatively strong correlation between UK investment and imports of goods and services, which were up 4.3% on year.

Along with the ongoing underperformance of UK exports of goods (also stressing the need for a trade reset with tariffs potentially coming down the pipe, along with a weaker currency), this meant that net trade was again a significant drag on UK GDP in the third quarter. This got very little attention.

Likewise, the latest PMI flash release for November (the UK’s composite output index of 49.9, compares with 48.1 for the euro area, 47.3 for Germany and 44.8 for France, although 55.3 for the US), highlighted weaker global economic conditions and intense competition in export markets, as well as reduced capital spending.

Saltmarsh Economics is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.