As things stand, no one should be surprised if there is more focus now on the establishment of new trading and supply chain blocs, globally, and the status of the dollar as, by far and away, the dominant reserve currency, also giving the US the ability to fund its large twin deficits relatively cheaply with capital inflows; in large part from Europe, not just China or Japan, as is still commonly reported - see here for one of our many earlier posts on the subject, “Chpt. VIII: The Queen’s Croquet-Ground”.

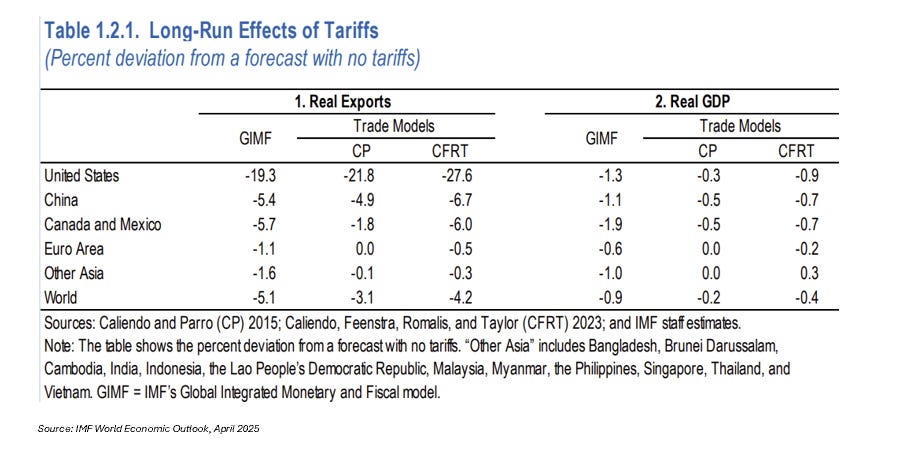

The IMF did not come out last week and call a global recession, but much of their analysis highlighted how the US could come off worse, and still be running a current account deficit of 3.2% of GDP and a government budget deficit of 5.5% of GDP, in 2026, with US government debt on course to hit almost 130% of GDP by 2030 (compared to just less than 100% globally).

All such forecasts come with a large margin of uncertainty, but in many ways are entirely predictable. Moreover, given all the current uncertainties about how exactly everything is going to pan out, when it comes to longer-term direct investment flows, it would not be so surprising if many foreign companies decided to seek out what may now appear to be more profitable opportunities elsewhere.

There has been some discussion about whether in a world of more limited trade barriers, more direct investment would be attracted to the country in question (the US in this case), to take advantage of increasing returns to scale, and what is still a large (potentially profitable) single market. But that is a very different world to the one we now find ourselves in, right now.

● One additional observation we would make is that, in contrast to the US today, with its very large current account deficit, and net external liabilities of almost 90% of US GDP, the UK was, at the height of the Gold Standard, internationally a substantial creditor - which it generated a significant income from (much of it, of course, from the US).

● By 1913, the net asset position of the UK was estimated at over 160% of GDP, a significant rise from the 1870s, with the UK running in contrast to the US today, a current account surplus of almost 10% of GDP. And, this was despite running a significant trade deficit in goods.

● But, of course, the Gold Standard was an example of a fixed exchange rate system, when the focus was (like Bretton Woods after it) on too much of the onus of adjustment being on the deficit countries (perhaps due to an overvalued exchange rate), rather than on surplus countries, potentially leading to a deflationary bias in the system (something that has also been an issue with the euro area).

● And being a rentier economy, where much of the UK’s income was derived from an increasing stock of international assets, led to its own problems - which are arguably still with the UK today.

But the point remains that we do seem to be at an inflection point of what could be rapid and significant change in the world’s monetary order.

We could also add that the counterpart of Germany running a large current account surplus in recent years (which has also been highly correlated with very low German bund yields), has been less German direct investment overseas, but buying of debt securities internationally. These, by their very nature, tend to be more shorter-term in focus, something perhaps for another post.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Saltmarsh Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.