A new asset class: Macro climate risk is not the same as ESG

Views From the Marsh - David Owen

Climate change economics is not the same as ESG, as recent events again highlight. A company might tick all the right ESG boxes and may be a low emitter (including Scope-3), but because of its location, will be exposed to more frequent and much more extreme climate related events, such as hurricanes or floods.

Such assets could well become stranded, with companies facing increasing issues raising finance or being insured; especially as regulators become more and more focused on the issue.

Hardly a week goes by without the ECB addressing the issue through speeches or working papers. Last week saw ECB Executive Board Member, Frank Elderson, give a key-note speech “Sustainable finance: from “eureka!” to action” (see here).

Elderson made the point that 2017 (when the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) was founded) marked a “eureka” moment for a group of central banks and supervisors, when they recognised that “if climate and nature-related risks are a source of financial risk, they fall squarely within the respective mandates of central banks and supervisors – to preserve price stability and ensure the safety and soundness of banks”.

The ECB is looking at the collateral framework that they apply to different banks’ participation in their lending operations. Penalties will be applied to banks who fail to compile with the deadlines set for them to address climate and nature related risks to their loan books, governance, strategy and risk management. And this is just the start of the process.

Last week also saw a paper delivered at a National Bank of Belgium conference, examining the economic impact of the July 2021 floods in Belgium (see here). This made the distinction between the direct effects on firms in the flooded area and importantly, those indirectly effected through the supply chain.

Given the central role that Belgium plays in what are now complicated European supply chains (the Belgium lead indicator was always held up as a timely barometer of what was going on more generally across the EU) such indirect effects could be very important.

Not surprisingly, the paper found clear evidence of strong and significant direct effects of the floods. Of those that survived, sales decreased, on average, by 15% and this negative effect lasted for at least three quarters after the floods. But when it came to indirect effects it mattered whether a firm was positioned upstream or downstream of the flooded firms. One percentage point more upstream exposure was estimated to decrease sales by almost 0.3%, with the effect persisting for at least four quarters after the shock.

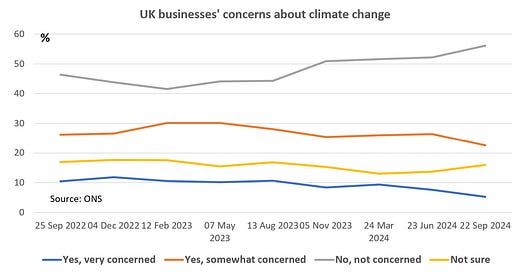

But this is not how many in the markets, or even many firms themselves, seem to view the risks stemming from climate change and natural disasters, as a survey conducted in September in the UK on the subject highlighted (see chart).

Please consider becoming a paying subscriber to continue reading on.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Saltmarsh Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.